Central Asia sees its economic future in China, not Russia.

China is a dependable, hands-off and generous partner when the times are hard. That was, in essence, the message that Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi had for his hosts during a tour of Central Asia this week.

The gist of that agenda was conveyed by his spokesperson ahead of the trip.

“Central Asia is facing new challenges due to various internal and external factors,” the spokesman, Zhao Lijian, told reporters on July 26. “Regional countries share the hope to deepen cooperation with China, jointly pursue development and promote security.”

Wang’s first stop was the capital of Uzbekistan, Tashkent, where he attended a meeting of foreign ministers of Shanghai Cooperation Organization member nations on July 28-29.

Since Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov was also present at the SCO event, however, it was his remarks that made most headlines. Lavrov told reporters that Moscow was holding fast to Beijing’s “one China” principle – in effect a rejection of Taiwan’s claims to statehood.

The remarks felt apposite at the SCO, a Beijing- and Moscow-led group whose purpose beyond the mutual exchange of reassuring bromides has felt increasingly difficult to discern.

Wang’s conversation with Uzbek Foreign Minister Vladimir Norov on July 29 was very much in that SCO spirit. Beijing, Wang said, strongly supports Uzbekistan’s efforts to preserve its national sovereignty and stability – an implicit reference to recent deadly unrest sparked by Tashkent’s now-scrapped plans to dilute the symbolic autonomy enjoyed by its Karakalpakstan republic.

China opposes any external interference in the internal affairs of Uzbekistan, Wang assured Norov.

When making such statements, Chinese officials are seeking to starkly distinguish themselves from the kind of stances adopted by Western governments, who often, although far from always, react to partner governments quelling protests with severe violence by pleading for independent investigations.

Following what unfolded in Karakalpakstan, for example, the European Union called “for an open and independent investigation into the violent events.” In an implied rebuke of Tashkent’s foot-dragging on political reforms, the EU in the same statement urged Uzbek authorities “to guarantee human rights, including the fundamental rights to freedom of expression and freedom of assembly, in line with Uzbekistan’s international commitments.”

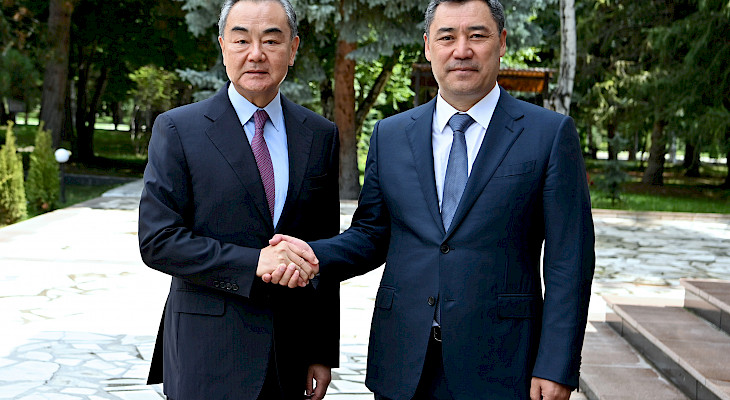

Wang was met with even more enthusiasm in Kyrgyzstan.

In remarks that might raise eyebrows in Moscow, Kyrgyz President Sadyr Japarov told his Chinese visitor during their meeting on July 30 that Bishkek views Beijing as its main economic partner on the international stage.

“This visit will become a bright historical milestone in Kyrgyz-Chinese relations,” Japarov’s office said in a statement.

Going by trade alone, Russia still retains a dominant position in the Kyrgyz economy. Where Russia and Kyrgyzstan did $2.5 billion in trade (most of it heading from north to south) in 2021, the figure for bilateral trade with China was $1.5 billion (almost all of it going east to west).

Foreign Minister Jeenbek Kulubayev indicated in a briefing before Wang’s arrival that closing that gap, which he said was to a considerable extent a consequence of the trade-sapping impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, was a priority.

“We [are struggling] to revive the potential that we had before the pandemic. Because of this, our entrepreneurs are suffering, the volume of trade has fallen,” Kulubayev was quoted as saying by 24.kg news agency.

Another matter to discuss, the minister forecast, was the money currently owed by Kyrgyzstan to China. As of June, Bishkek’s liabilities before the state-run Export-Import Bank of China, better known as Eximbank, stand at almost $1.8 billion.

The Kyrgyz leadership is candid about how it sees China driving its future prosperity.

As Japarov told reporters after his meeting with Wang, the Kyrgyz government is aligning its “development strategy with China’s One Belt, One Road initiative,” better known in English as the Belt and Road Initiative.

Getting down to specifics, Japarov expressed pleasure at China’s pledge to fully underwrite a major new piece of infrastructure, the Second Chui Bypass Water Canal, known by the acronym OChK-2, with a grant.

He also returned to a topic much favored by Kyrgyz officials of late: the long dreamed-of China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway route. Japarov suggested that a document tentatively committing all sides to this project could be signed at an SCO summit due to take place in Uzbekistan’s city of Samarkand in September.

“The head of state expressed the opinion that the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway would be an important addition to President Xi Jinping’s One Belt, One Road initiative,” the statement from Japarov’s office helpfully volunteered.

Chinese engineers have already pitched up in Kyrgyzstan to begin survey work for the railroad, Japarov’s office said.

Wang completed his tour in Tajikistan.

Few are as beholden to China as Tajikistan. Of the $3.3 billion that Dushanbe owed to international creditors at the start of 2022, 60 percent – $1.98 billion – is owed to Eximbank.

It was perhaps redundant then that Tajik President Emomali Rahmon should have tried on August 1 to charm Wang with his remarks about wanting to see “a further deepening of close multifaceted relations … in every format.”

As with Kyrgyzstan, the restoration of trade volumes is seen as a priority for Tajikistan.

“Statistical data indicate that bilateral trade turnover grew almost 82 percent year-on-year in the first half of this year [as compared to the same period in 2021] to make up more than 19 percent of all of Tajikistan’s foreign trade turnover,” Rahmon’s office said in a statement following his meeting with Wang.

But that is not enough for Tajikistan.

“It is necessary to take joint steps to increase the pace of trade,” Rahmon’s office said.

Eurasianet.org,

1 August, 2022