They say money can’t buy happiness, and that may be true for Central Asia.

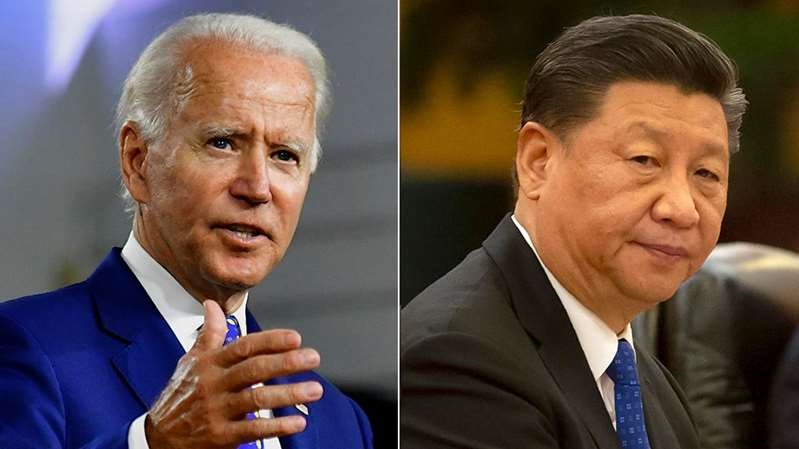

U.S. president Joe Biden recently suggested that democratic countries set up an infrastructure fund to counter China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The U.S. previously criticized BRI as a way to use “debt-trap diplomacy” to extend China’s influence over developing countries, but it hasn’t been able to dissuade borrowers from dealing with China.

There’s been pushback against the “debt-trap diplomacy” concept and recent research has shown the Chinese are tough negotiators and can cancel a loan if a borrower takes an adverse political stand, but there’s no “smoking gun” evidence of a predatory program behind China’s loans.

There is an existing infrastructure fund for Asia, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) but the U.S. declined to join it in 2015 – when a man named Joe Biden was vice-president. Washington was concerned the AIIB would compete with the World Bank and extend China’s influence – and it tried unsuccessfully to persuade allies like the UK, Canada, and Australia to not join.

The U.S. has criticized China’s lending policies, and refused to join the AIIB, but has supported lending to Central Asia through the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, the World Bank, and the other multilateral development banks (MDB), such as the Asian Development Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and the Islamic Development Bank. The questions are, then: Is Biden’s mooted project new money or repackaged old money? Will the money be another funding option or just an alternative to Chinese loans?

The United States Strategy for Central Asia 2019-2025 has as an objective to “Support and strengthen the sovereignty and independence of the Central Asian States.” One way to honor this commitment is to ensure the states have flexibility and discretion in working with lenders to ensure the lending satisfies all parties’ priorities and is spent efficiently and effectively.

The Central Asian governments can respond to Biden and force the pace by approaching the lenders with their regional plan for the lenders’ money, which can highlight overlaps and inefficiencies, and recommend where money can be reprogrammed. This will have to take account of lender preferences, such as the Scandinavians’ interest in women’s issues or the U.S. interest in health. This will also acknowledge that many issues such as water and air quality, or public health, don’t stop at one country’s borders.

As to the money, if it is an option to Chinese funds it will give the states the opportunity to shop around to country lenders or the MDBs to get the best terms. The states can use this to create external constituencies for their success and also give their officials exposure to a range of lenders in North America, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. If the money is a take-it-or-leave-it alternative to China, Western lenders may find the locals will pass.

Researchers at Ghent University found that development assistance from the European Union often “fails to have a significant impact” while aid from China “is more pervasive, and has a tangible impact on the ground” but that is “offset by the negative implications of its increased involvement, including deepening economic and financial dependency.” So, the Central Asian leaders are likely keeping a weather eye on China, but regional polls indicate that “Russia enjoys evident dominance in public opinion, China is in a relatively well-regarded second place, and the U.S. comes in decidedly last.” Thus, the local leaders have public support for “shopping around” so long as they ensure that sovereignty and independence are respected by the lenders.

The last will collide with the Western view that Chinese (and Russian) funds are “bad” and a dose of Western support will set things right. The local view is that, as they are finally independent since their absorption by the Russian Empire in the early 1800s, they won’t trade bosses in Moscow for bosses in Washington, Beijing, or Brussels.

The U.S. tends to view Central Asia only in relation to other issues: stabilizing Afghanistan, blunting China’s BRI, checking Russia in the “near abroad.” Since America won’t likely change its spots, and has big bills to pay for domestic and infrastructure programs, it should stop wasting time regretting the Belt and Road not taken. China’s leaders think Central Asia holds “extremely great geopolitical strategic value,” so Beijing made a bet and will reap the rewards.

The wise choice for America is to be the “financial balancer” and ensure there’s always a competitive financing option available to what it considers predatory lending, and that Russia, Turkey, and China (and eventually Iran) can’t exclude any third party from investing in Central Asia.

The U.S. should also continue to support the Central Asia 5 plus 1 (C5 +1) process – but it will be dollars on the ground that matter most.

It’s usually a bad idea to follow the example of Communists, but as they deal with Western complaints about China’s infrastructure investments, local officials should recall the core consideration of Afghanistan’s Reds: Does that ideology come with electricity?

“The Hill”

James Durso

07.04.21